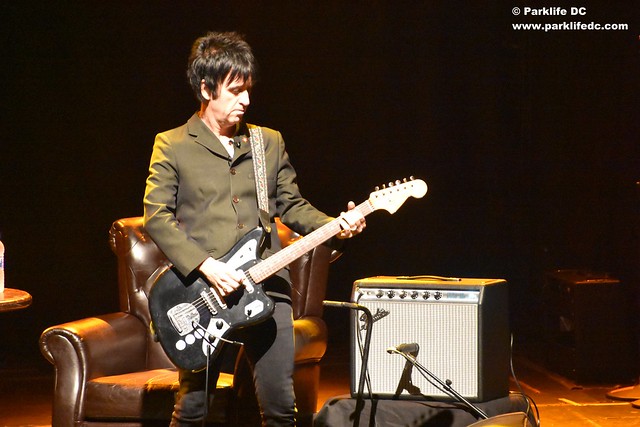

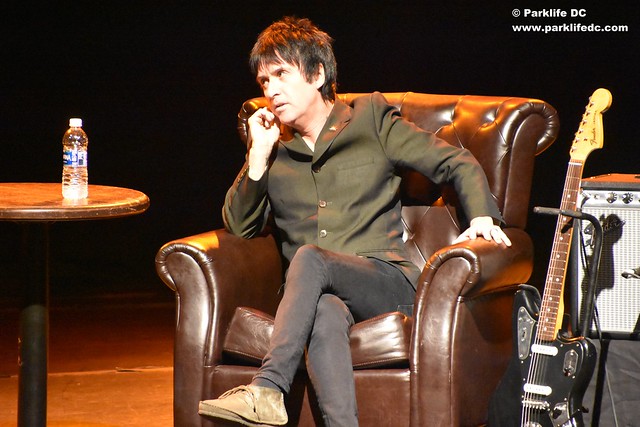

Johnny Marr and his guitar at New York’s Gramercy Theatre on Nov. 15, 2016. (Photo by Mickey McCarter)

Johnny Marr and his guitar at New York’s Gramercy Theatre on Nov. 15, 2016. (Photo by Mickey McCarter)

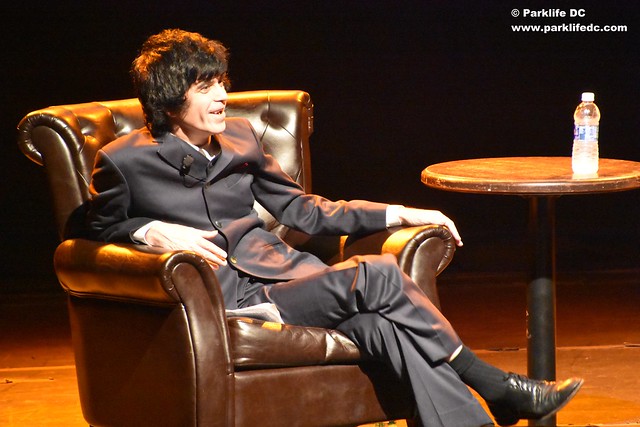

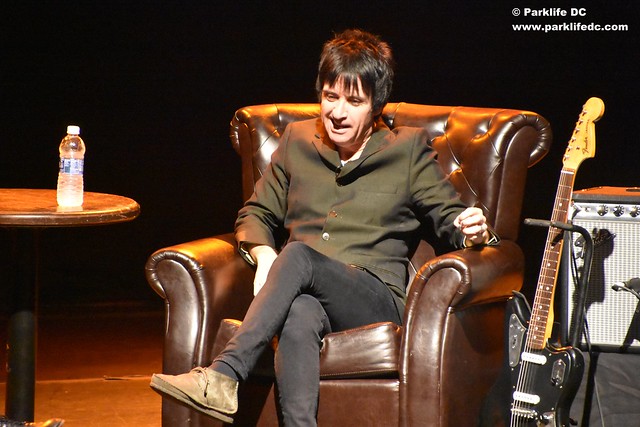

Johnny Marr, surely the world’s most famous living guitar player for us in Generation X, released his autobiography “Set the Boy Free” in the United States last month, and he delivered a book talk with DC indie rock musician Ian Svenonius as host at the Gramercy Theatre in New York City on Nov. 15, the day of the US release. I was there, and now I’ve finished reading the book.

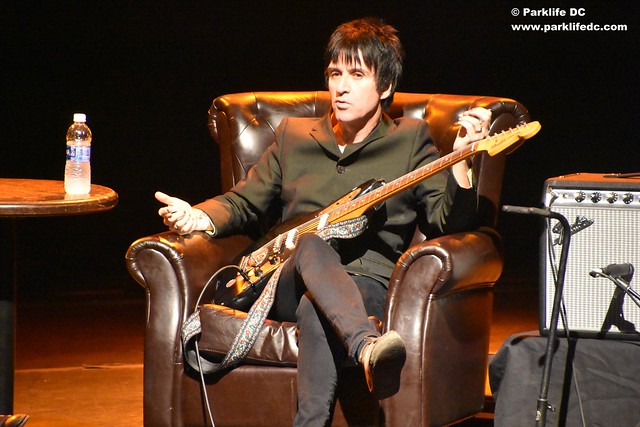

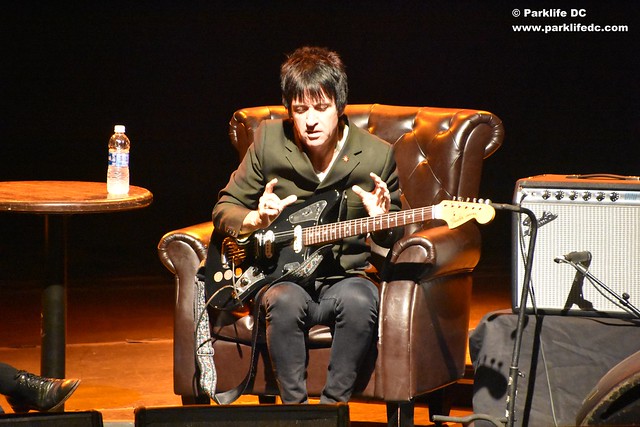

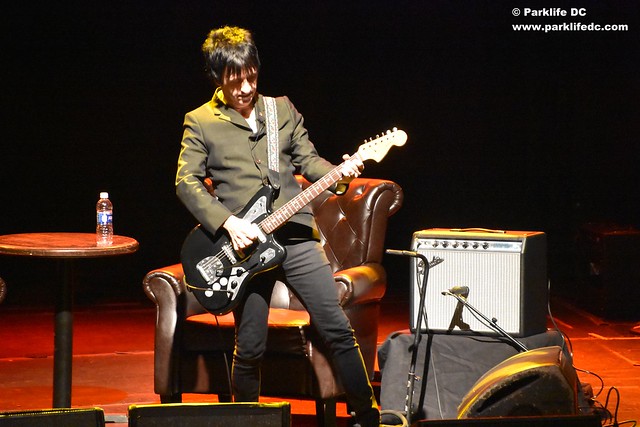

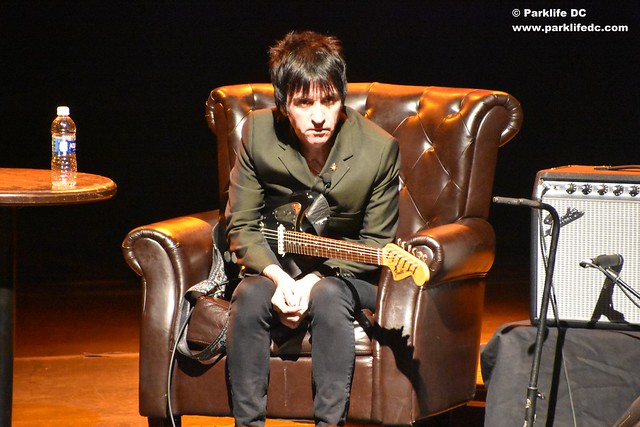

During the book talk, Johnny came equipped with a guitar, which he plugged in and played on occasion to highlight or underscore various memories. A lot of his reminiscing centered on his time as a very young man learning the guitar and growing up in an extended family household of Irish folk living in Manchester, England. This is the strength of Johnny Marr’s book. [And it is key to being introduced to Joe Moss, the first manager of The Smiths, and latter-day manager of Marr; you won’t fully understand Johnny if you don’t know anything about this man.] It is important to remember also how Johnny came from humble beginnings to being a hero to millions, all because he had a guitar in his hand and he knew what to do with it.

In his Nov. 15 book talk, the most revelatory moments come through music. Johnny demonstrated how “Rebel Rebel” by David Bowie was one of the first songs he learned to play. He ably threw the guitar riff out to our audience. But then he demonstrated live how “Hand in Glove,” one of the first songs he ever wrote, fit within the groove of that Bowie masterpiece.

A lot of Johnny’s book dwells on his time as a young man, a happy time where he grew up with loving parents and siblings, but more importantly a time where he absorbed all of the music his mom, sister, and others would play, ranging from Irish folk to glam to disco (disco particularly in the form of master Nile Rodgers, in this blog’s opinion, the world’s best living guitar player — a sentiment with which we suspect Johnny Marr agrees).

So it’s fascinating to read about how the Maher family (Johnny’s original surname) would host relatives at their house for a big dance party and how by the end of the night, the songs would go from jaunty to maudlin. And it was memories of those maudlin Irish tunes at the end of the night that inspired Johnny to hammer out the music for “Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want,” which earned its name when his songwriting partner [Steven] Morrissey wrote the lyrics over the tune for their band The Smiths. (The song originally appeared as the B-Side to “William, It Was Really Nothing” and became known to many Americans for its inclusion in the soundtrack to the movie Pretty in Pink.) I would honestly say you are right there in the excitement together with Morrissey and Marr when Johnny writes of his shared experiences of songwriting with Moz.

Quite a bit has been made in reviews from outlets like Pitchfork and The Washington Post by the stylistic (and maybe personally political) differences between the memoirs by Johnny Marr and Morrissey. But both of those outlets, at least, misunderstand the working relationship between the two and how their books demonstrate the manner in which their strengths augmented one another.

Johnny Marr’s book is straightforward and nostalgic. But wherever Johnny lands, he does so with a sense of his destiny.

His writing is very much evocative of how many folks, including self-taught Johnny, learn to play guitar. They put chords together, form patterns, and write songs. On the other hand, Morrissey’s autobiography (“Autobiography”) is similarly representative of the thinking of a lyricist. He’s flowery, poetic, and compulsively non-linear. While it’s true that Morrissey’s book may be a more compelling read, you would not understand The Smiths or the partnership between Morrissey and Marr without first comprehending how they clicked and how one filled in the gaps for the other.

Much has been made of the eternal question — will The Smiths reunite? For those who understand how Johnny thinks, you can parse his language. It’s not entirely up to him, but he would be game for it under the right circumstances. (That’s a more definitive answer than his reflexive “Google it,” which he offers in response to a string of interviews in his book.) And if you read what he wrote, it’s a lot more open-ended than when The Guardian posed the question of whether Marr and Morrissey might reconnect. Johnny’s answer then: “I think it’s run its course.” While I respect the answer of a working musician, I honestly don’t think that’s the end of the story.

As evidence, I suggest an oft-discussed passage in Johnny’s chapter, “The New Fellas,” dedicated largely to his collaboration with UK punk band The Cribs. In 2008, he and Morrissey met to catch up, and the question of reforming The Smiths arose.

As Johnny writes in the book, “It was definitely nice to be together, and then suddenly we were talking about the possibility of the band reforming, and in that moment it seemed that with the right intention it could actually be done and might even be great.” The right intention, as implied, would be the two principals of the band — Morrissey and Marr — would like to work together again and make great music. This is offered in contrast that some entity might offer millions of dollars for them to reunite for a show.

At the time, Johnny was entering into a working relationship with The Cribs, with which he would be in a band for the 2009 album Ignore the Ignorant. Johnny spells it out in his book: “I would still work with The Cribs on our album, and I made it clear that I’d do that first, and Morrissey also had an album due out.”

After that September chat in a Manchester pub, where Moz drank up beers and teetotal Johnny drank up orange juice, the two hugged and suggested they would re-approach the subject again. But for Johnny, a possible reunion came with a very real reinterpretation of The Smiths. In his book, he underscores, as does Morrissey, that The Smiths are truly the partnership of Morrissey and Marr — and no one else. In a reunited version of The Smiths, Johnny’s boyhood friend Andy Rourke would likely find himself welcome again as the bass player. But drummer Mike Joyce, who pursued court action against The Smiths for exclusion from the band’s partnership, would be out.

Morrissey dedicates a healthy quarter (perhaps my exaggeration) of his autobiography to the ’90s court case that Mike Joyce filed against himself and Johnny. Johnny deals with it in a single neat chapter. That said, the two auteurs are in agreement — Mike Joyce had no case and would not be involved in any future projects despite the ultimate court ruling against Morrissey and Marr.

“I was genuinely pleased to be back in touch with Morrissey, and The Cribs and I talked about the possibility of me playing some shows at some point with The Smiths. For four days, it was a very real prospect. We would have to get someone new on drums, but I thought that if The Smiths really wanted to reform at that point it could be good and it would make a hell of a lot of people very happy, and with all our experience we might even be better than before,” Johnny wrote.

“Our communication ended, and things went back to how they were and how I expect they always will be,” he said.

“Set the Boy Free” by Johnny Marr was released on Nov. 15 in the United States by Dey St., an imprint of William Morris, HarperCollins Publishers. It was originally published in the United Kingdom by Century, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Buy Set the Boy Free: The Autobiography by Johnny Marr on Amazon.

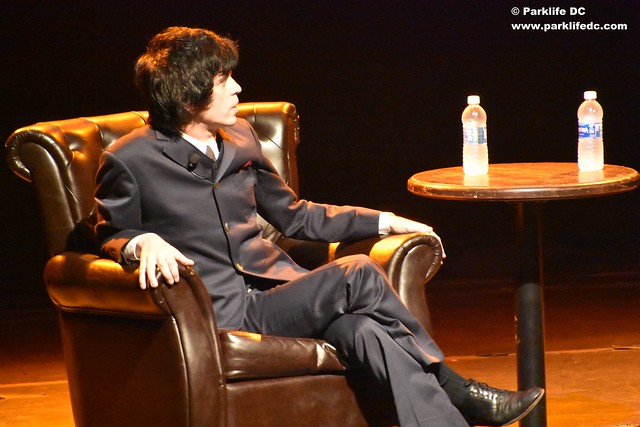

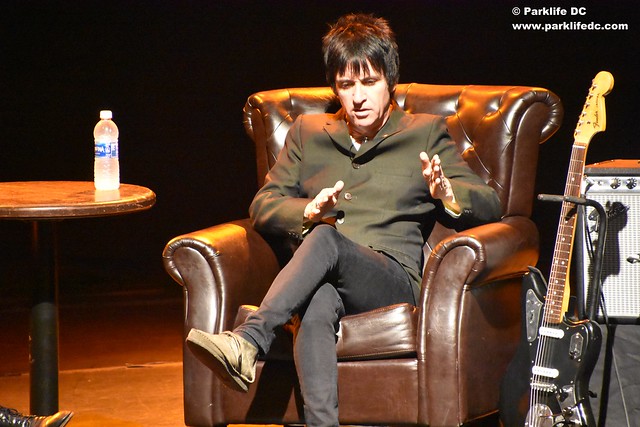

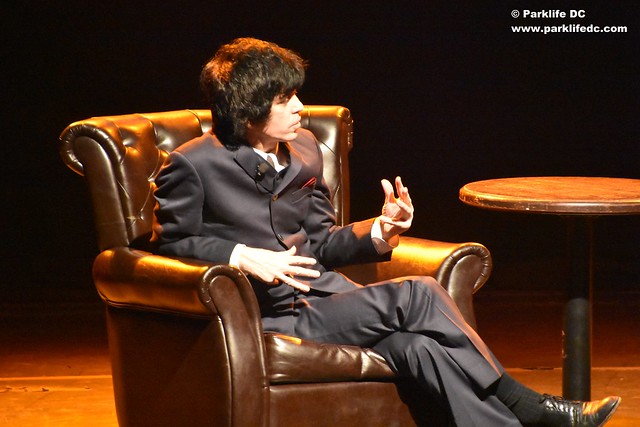

Here are some more pictures of Johnny Marr being interviewed by Ian Svenonius at the Gramercy Theatre in New York on Nov. 15, 2016.