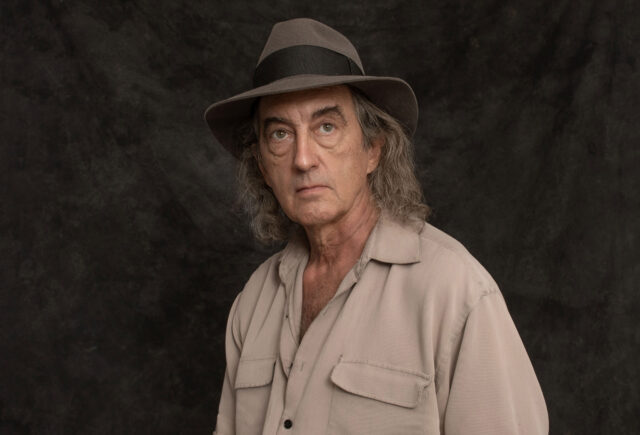

James McMurtry on Politics, Language, and His New Album, The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy

Interview by Mark Engleson

James McMurtry is angry. “We’ve got the Gestapo, now,” he tells me, “Only we call it ICE. And they’re disappearing people.” I mention how, when I saw I’m Still Here, the film about the disappearances in Brazil in the 1970s, I turned to my date after the movie and said that was America’s future. I wish I hadn’t been right.

(There is one difference: The Germans were far more organized than these ICE clowns can ever aspire to be. They wouldn’t have accidentally sent someone to a Central American gulag because of a clerical error — they would’ve done it deliberately and known exactly where he was at all times.)

McMurtry has never been afraid to take a stand on issues, in both his songs and his actions. He’s written songs like “Cheney’s Toy,” a devastating takedown of then-President George W. Bush. When he played in the DC area last year, he gave the audience a preview of “Sons of the Second Sons,” which he recorded for The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy — released in June to some of the strongest reviews of his career. The song explores the role of primogeniture in shaping the class structure of the American South through the voice of one of those sons.

Stream “Sons of the Second Sons” by James McMurtry on YouTube:

Last year, while performing Tennessee, McMurtry defied the state’s ban on performing in drag by switching outfits with his opening act, BettySoo, to perform a duet in his encore. I mention to James that he doesn’t strike me as being particularly cowed by authority or external pressure. “I wasn’t afraid to do that,” he said and added, “My band was afraid for me.” It worked out for the best, he says, as it resulted in him getting coverage on Rachel Maddow’s show on MSNBC.

While James is not afraid to write songs that take a position, he told me he tries to avoid being didactic, preferring to work through the point-of-views of the characters in his songs rather than injecting his own opinions. (Some of the worst pieces of fiction I’ve read — and I’ve been shocked how highly regarded some of these are — have been stories that ceased to be narratives and became treatises.) “Steve Earle is a genius at that,” he tells me. As James likes to say, “A good old boy can become an intellectual, but an intellectual can’t become a good old boy.” Earle has a common touch — I once heard him say that people in West Virginia opened up to him “because I talk like this” — which contrasts with McMurtry’s background: His mother was an English professor, and his father was the celebrated novelist and screenwriter Larry McMurtry, who wrote Lonesome Dove and adapted the screenplay for Brokeback Mountain.

The elder McMurtry was part of a celebrated MFA class at Stanford that also included Ken Kesey (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest), the fantasy writer Peter Beagle (a personal hero of mine, best known for The Last Unicorn), and the feminist science-fiction writer and critic Joanna Russ. When James was very young, Kesey and his band of hippie followers, the Merry Pranksters, would often visit. After Larry passed in 2021, James found a pencil sketch from the ’60s, which his stepmother believes was drawn by Kesey. That drawing inspired the titular song of his latest album, The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy. James follows the advice given to artists not to read reviews of his work. When I say he must be pleased with what people are saying about the album, he replies, “What are they saying?”

Speaking of bands, when McMurtry rolls into The Birchmere on Sept. 18, he’ll be coming with a full band. It’s his first full band show in the DMV in a long time. He normally performs solo and acoustic, having “learned to tour cheaply.” I ask him if he chooses the set differently for a full-band show, and unsurprisingly, he says, “It makes the rockers easier.” I also note I’ve always seen him play at The Birchmere, and I ask if he has a sentimental connection to the venue. What it comes down to, though, is, “They always make me a good offer.”

McMurty isn’t sentimental. He’s said he’s really a beer salesman “and I’m okay with that.” He always makes a point of telling his audience to tip their servers, “Starting at 20% and going up from there.” He does have a connection to this area, having grown up in Loudoun with his mother, who introduced him to the guitar, and his stepfather.

On The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy, he covers Kris Kristofferson’s “Broken Freedom Song.” I asked him how much of this decision came down to the similarities in their singing voices. He went a different direction, telling me how Kristofferson was the first artist who was introduced him to as a songwriter. It was also one of the first concerts he attended, when he was about nine years old.

Speaking of his days in Virginia, McMurtry has good things to say about his time in high school, was relatively of free cliques. He says he could’ve taken better of advantage but, “I was an angry kid.” I was, too, and it usually didn’t work out to well, because I was the smallest guy in my class.

The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy opens with another cover, fellow Austin musician John Dee Graham’s “Laredo.” Graham has been in and out of the hospital dealing with serious spinal problems. (As a fellow survivor of multiple spinal surgeries and a MRSA infection, I send out my best wishes to John on his recovery.) McMurtry and his band worked up the song for a benefit, so they were able to record it as “a happy accident.”

Stream James McMurtry’s cover of “Laredo (Small Dark Something)” by John Dee Graham on YouTube:

When they went into the studio to record with producer Don Dixon, James and his band cut 13 tracks, whittling down the record to 10. I ask if this typical of the process; James tells me they normally record 10 songs to get 10 tracks.

Though he spent some 30 years living in Austin, McMurty left the city a few years ago to move to Lockhart, a small town about 30 miles away. “We got priced out,” he tells me, echoing what I’ve heard from other musicians. I ask how he likes Lockhart; he says prefers a bigger city, but it does have the advantage that he can get right on the highway. “At least until you hit the Kady Freeway in Houston,” I say. He replies that Houston isn’t bad, that “they know how to drive there. It’s like Los Angeles: They understand the automobile.”

This many years into his career, I ask if the writing process has changed for him. “Not really.” He explains that he often starts with a single line and a melody. I’ve found this often happens with short stories for me, and I mention the similarities between the forms in their emphasis on economy of language. McMurty shares his belief that it’s harder in prose, and he tells that “Larry never did figure it out.”

Given the milieu he comes from, it’s not surprising just how important language is to McMurtry. He puts down the idea of making English the official language of the United States, “It seems like very few of us speak it, and even less can write it.” We share a similar love of wordplay in humor: He tells me about how, driving on the highway in Oklahoma, he saw a sign that said, “Hitchhikers may be escaping inmates.” I knew exactly where this one was headed: “We didn’t see any hitchhikers. The inmates must have got them.” I shared this with my friend Steve, a fellow McMurty fan, and he smiled and nodded, saying, “Sounds like something you would say.”

James McMurtry appears at The Birchmere on Thursday, Sept. 18, backed by a full band, with BettySoo opening the show. Don’t miss the opportunity to see one of American’s greatest living songwriters.

James McMurtry

w/ BettySoo

The Birchmere

Thursday, Sept. 18

Show @ 7:30pm

$53.30

All ages