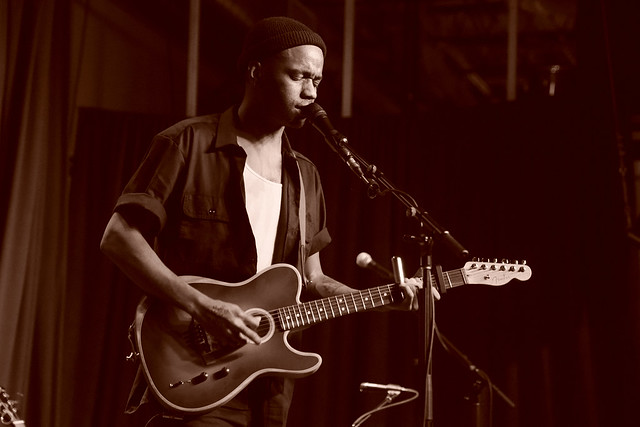

Carl “Buffalo” Nichols performs at Songbyrd Music House in Washington DC on Nov. 9, 2021. (Photo by Casey Vock)

There’s admiration to be had for anyone who sets out to prove a point or to tell an important story with their music.

On a mission that is most certainly catching the ears of astute listeners and those who care about celebrating the history and sounds of traditional music, Buffalo Nichols should be applauded for the progress he’s making and the sound he’s creating. And, making an appearance last week in the nation’s capital at the newly relocated Songbyrd Music House, he showed that he’s emboldened by a workingman’s conviction and possesses a vision for how his songs can make an impact.

Carl “Buffalo” Nichols was born in Texas but spent his formative years in Milwaukee, where he struggled to look past racial differences and inequalities and where he couldn’t find the right outlet for himself as a young guitar player, one who’d occasionally skip school to give himself a day alone to practice.

Still, Carl kept the guitar in his hands, and he cut his teeth playing in a variety of outfits, making his way into the local music scene through the church, and then finding pathways to join a range of bands. While those roles didn’t result in stardom, they certainly helped put him on a trajectory to find himself as he would eventually make his way across the oceans to places like Africa and Europe.

Watch Buffalo Nichols’ Live In Mississippi performance of “How To Love” via his official YouTube channel:

Nichols recognized how important black music was to the world, but that back home in the United States, so much of its history and meaning is lost on listeners today, even though the work and creativity of black musicians has touched so much if not all of the songs we hear in our daily lives.

He became zealously motivated to pay deeper respect to the blues, music he’d responded to the most as a teenager picking through relatives’ records collection and spinning all he could. And after witnessing the tumultuous chain of racially dividing events that have defined the current climate in America, Carl made the decision to go solo as an artist — walking away from Nickel & Rose, a Milwaukee-based folk duo he previously co-led that as the pandemic struck was just starting to land gigs at notable festivals.

Altering his plans, relocating to Austin and digging in to hone his own blues voice and guitar sound, Carl would spend the last couple years channeling his energy, his hope and even some anger into original compositions that would ultimately land him a deal with Fat Possum, becoming the label’s first individual blue artist to sign in almost two decades.

On tour promoting his premiere album as Buffalo Nichols, Carl provided a promising set of music on Nov. 9 in DC that pulled from the self-titled debut, but also saw him perform some blues favorites, as well as some songs that have yet to be recorded to an album, showing promise for an artist who wears his determination on his sleeve, who doesn’t hide his frustration with the industry.

Stream Buffalo Nichols’ self-titled Fat Possum premiere via Spotify:

“Lost & Lonesome,” his opener at Songbyrd, is an ageless, destitute ballad galvanized by Nichols’ countless hours traveling alone abroad and stateside, feeling excluded or only briefly attached to wherever he might have been — valuable, even if challenging experience for his head-first plunge into the blues. Authentic in its painful search for connectivity, the track showcases his deep, graveling texture through the mic and his instinctive, restless fingers pulling radiance from the strings and body of his shimmering resonator guitar.

“If you see me in your town

Looking tired with my head hanging down

You may wonder what went wrong

Why am I always all alone?

Why am I always all alone?

Well since I could remember

I’ve been wandering on my own

Looking lost and lonesome

since I left my mother’s home.”

Nichols’ resolve is loud and clear in his first album, an offering that should appeal to a range of listeners, even if they don’t fully grasp what it stands for. And what it represents is a human who’s bridging past and present — providing a sonic window to songs rooted in Black hardship, expression born out of the disadvantages and challenges Black people in America have historically faced and that unfortunately they still battle today.

By writing fresh songs built with blues guitar foundations established long ago, and by more clearly focusing their narrative on Black people, Buffalo Nichols is creating a link that helps extend all the way back in time to the original blending of African folk traditions that took place in America beginning in the 1600s.

On stage at Songbyrd, his attitude was an endearing form of surly, and he smoothly asserted controlled over the room. Nichols appeared steadfast and unapologetic about his effort to remind people that the blues is in fact a contribution of Black musicians and his pledge to forge songs that speak to and commemorate Black life in American today. Making little eye contact throughout the set, his words sometimes quick and short but undoubtable, his presence both convincing and daring

“Y’all mother fuckers got in for free,” Nichols said, immediately bringing levity to the space where onlookers were quiet and seated at tables. The show, which was in fact free, was scheduled short notice in between gigs on Buffalo’s current tour, a well-timed appearance as he looks to build on his current momentum that already has garnered him more than 100,000 monthly Spotify listeners.

Listen to the official audio of Buffalo Nichols’ 2021 single “Lost & Lonesome” via his official YouTube channel:

“How To Love,” another ear-pleasing standout from his record, translated to an awakening, resonating rhythm enhanced by a thumping, measured stomp coming from an electric bass drum pedal Buffalo kicked while playing his guitar with a slide and while belting out lyrics that, though swift and heartfelt, were still agonizing:

“You know a pretty girl will make you do ugly things

Like smoke cigarettes and buy diamond rings

I know I am not a heartless man

There’s some things I hardly understand

Well, there’s one thing you did that’s good for me

You showed me things that I just could not see

Made me realize I do need love

Even though in the end I wasn’t good enough

The way you hurt me showed me how to love.”

A gut-wrenching slice of the profound songwriting ability Carl has tapped into early on this quest, “These Things” is a touching, luscious track with rustic folk qualities that benefits from sweet violin accents on his album. Stripped down for its live delivery with a Fender combo acoustic-electric, the track’s words languished and were stunning and poignant with dejection.

“If I could be up there with you

I would only tell the truth

And if it hurts like pulling a tooth

Then it only hurts one time

Well, I’d protect you from their lies

But the ones I’d tell would fly

So, they’ll end up above our heads

To feast on a love that’s dead …

With your body close to mine

And my heart in your hand

If we’re going to die together

Let’s do it to the rhythm of the band

And I dance to your beating heart

And you’ll dance on my grave

Just promise that you’ll break my neck

When you know I can’t be saved …

From all these things.”

Having already impressed with his first half dozen songs, Buffalo pointed to his left, where a stool and additional microphone suggested what was next.

“Now I’m going to go over there and play some blues songs — thank you, people,” Nichols said matter-of-factly, met with snorts of laughter from attendees who were keen to his humor.

“I just put an album out on Fat Possum, and they said I better play some blues.”

Performing an intentional culling of blues standards, changing guitars along the way, Nichols educated the room on some of his most important influences through his own version of “Statesboro Blues,” written by Blind Willie McTell and recorded in 1928, and his take on “Oh Death,” a song Charley Patton recorded in the 1930s.

“I just recently heard Charlie was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame,” Carl said. “That’s like putting the cart before the horse.”

He stopped himself from a tangent, but his mannerisms were consistent with the spirit of his music — to help open eyes to how underappreciated some of the most significant songs of our past has become, and then correct that issue by sharing and enjoying it today.

Nichols added a slide-heavy Muddy Waters cover, telling the audience “if you want to learn about it, visit your local library.”

Returning to his feet to close out the set, Carl grabbed his electric guitar for the provocative track “Living Hell” from his album, one of the more treacherous of the recording.

And a sampling of what’s to come, he rendered a stirring, wistful melody underneath bare, pleading words that he’s titled “Friends,” which isn’t yet on a record but will be down the line. It wasn’t his only unreleased song of the night — earlier, he shared “Life Goes On,” which had the crowd grooving in their seats and on their stools, whooping in approval during and after the song’s finish.

Carl, or Buffalo as he’s going to become known far and wide as he goes, is proud of the music that influences him, and you could see it in every strum, every move he made at Songbyrd.

Refined as a guitarist and vocalist, dedicated to honoring and repaying those who came before him and remarkably cognizant of today’s Black musicians, Buffalo Nichols has put in years of drudgery, sacrifice and struggle to organically evolve into a bluesman.

With a gift for captivating and impacting the minds of his listeners, Nichols has positioned himself to inspire countless other young Black musicians to explore and embrace the traditional sounds of their ancestors.

Here are images of Buffalo Nichols performing at Songbyrd Music House on Nov. 9, 2021. All photos copyright and courtesy of Casey Vock.