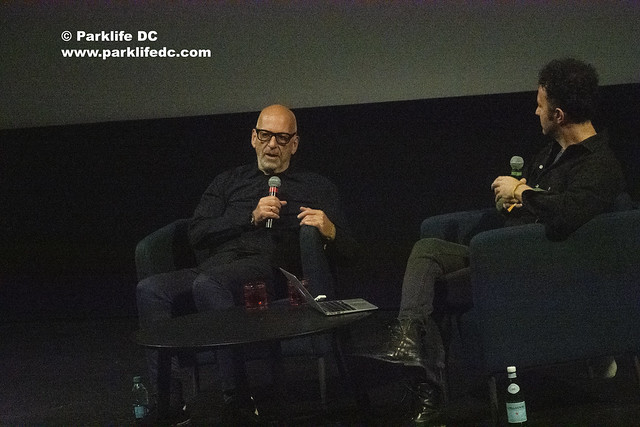

Daniel Miller chats at Moogfest 2019 in the Carolina Theatre on April 26, 2019. (Photo by Mickey McCarter)

To commemorate the 40th anniversary of his label, Mute Records chief Daniel Miller chatted with musician and writer Alex Maiolo in a conversation at Moogfest 2019, held in an auditorium of the Carolina Theatre recently. During Moogfest, Daniel also performed two DJ sets — a pure techno set at the comfortable Fruit Company club and art space and an ambient set on modular synths at the 21c Museum Hotel in Durham, North Carolina.

Alex’s enthusiasm sparked Daniel’s brilliance, and the musical svengali reflected on his early days as a musician, how Mute came to be, and his enduring love of synthesizers.

Visit the Moogfest website for more information on the Moogfest conference and festival.

Earlier in the day, Daniel interviewed Martin Gore of Depeche Mode, and the band recurred in conversation. But Daniel truly brought it home when recounting the origin of his pseudonym Silicon Teens with his cover of “Memphis Tennessee” by Chuck Berry.

Daniel said he had a vision of four teenagers who were an electronic band, contrasted to young teen heartthrobs with guitars, and that was the inspiration for him inventing a quartet called Silicon Teens and naming the players although the band was really only Daniel. In 1979, he released the Chuck Berry cover at Rough Trade’s suggestion, and recorded a few more songs as Silicon Teens. But his vision was truly complete when he met Depeche Mode the following year as they were truly four teen boys with synthesizers.

“Depeche Mode were pretty much the worlds first, kind of all over, teenage pop band,” Daniel said.

Stream “Warm Leatherette” and “TVOD” by The Normal on Spotify:

In 1978, Daniel recorded an electronic post-punk song called “Warm Leatherette” under the alias The Normal, which began his relationship with the Rough Trade record shop. He took his single to Rough Trade, and the bosses there played it live on the air on the spot — and they loved it. Daniel thought he might press 500 copies but Rough Trade asked for 2,000 to distribute throughout independent record stores.

“So they played it in the shop, and then it was kind of a meeting place as well. There were journalists there, and musicians, and I thought ‘Why don’t you just put some headphones on or something,’ I don’t want people to hear the record. They liked it, and they offered me a distribution system, which was quite an underground distribution through other independent shops, and they offered me a distribution deal,” Daniel said.

He continued: “Then very soon after my single came out, it became apparent there were a lot of people, people like me all over the country, who had gone through the same process that I had and you know there’s The Human League’s first single, so all of a sudden, in the space of two months, it just happened.” And an electronic scene had been created in England.

Still, Daniel had slapped his address on “Warm Leatherette” and made up the name Mute Records to give his recording some authenticity. He did not expect that people would begin to contact him through the address on the single.

“I had no intention of starting a record label. I just wanted to go out on the scene. So I got some things that were kind of interesting, but I mean I didn’t want to start a label so I wasn’t doing anything with them. Then there was a guy called Edwin, he was a writer and a cartoonist, he was a pop-punk cartoonist at the time for Sounds, and he had somebody he was sharing a flat with called Frank Tovey.”

“Edwin said ‘Oh, I’ve got this guy, I’m trying to get rid of him, he’s taking up too much space in my flat.’ Well, maybe if he gets a record deal, he will leave. I said, ‘Well, okay I’ll have a listen.’ I immediately related to the music, and I met Frank, and we got on really well. That was kind of the trigger for me to start the label.”

Daniel helped Frank make his first single, “Back to Nature,” as Fad Gadget, and thus began an artistically fruitful relationship.

Stream The Best of Fad Gadget by Fad Gadget on Spotify:

Inspired by the increasing accessibility of synthesizers, which had been prohibitively expensive through the early ’70s, and enthused by the DIY nature of the exploding punk scene, Daniel crafted a label centered around synthesizers and electronic music.

Alex asked Daniel if there were a Year Zero moment where a musical vision became clear to him.

“Well, there was a couple of Year Zero moments, I think. I think the first Year Zero moment was when I first heard CAN, which sounded like nothing else I’d ever heard before but sounded like I could really relate to it. And then all of what was known as krautrock, which is a term that I really hate, but a lot of the artists who were coming out of Germany in the late ’60s, early ’70s, were kind of rewriting German musical history. Or, not rewriting, reinventing. It was not really influenced by American or British blues-based music,” Daniel said.

He added, “Then punk, which was another Year Zero moment, and then came the DIY ethic of people coming out on the scenes, because it was very easy to do.”

In a humorous exchange, Alex agreed the term “krautrock” was disagreeable.

“The term krautrock is an extremely lazy term. If you were to take Genesis, and say Status Quo, and Thin Lizzy, and David Bowie, and you said, “Well, it’s ‘limeyrock,’ you know?” he quipped.

Daniel chuckled in response but returned with a sincere observation: “I think what was happening in Germany in the end of the 60’s was much more motivated, and of course, the whole rebuilding Germany, not just physically build but cultural rebuilding of Germany after the Second World War, had big impact not just on music, but on art, and films, and everybody.”

“You know, there were people who kind of wanted to create the new German Culture. Not that they would deny the culture of German culture in the past… they absolutely felt they needed to break from that and create something new. Artisans and filmmakers like William Dieterle, CAN, Noise, Faust. They were all kind of inventing something that was very specifically German, in the sense, aesthetically. Even though they were doing different things, they came from a similar group.”

Alex observed that a lot of English artists, including Daniel and Depeche Mode, eventually decamped to Germany, and specifically Berlin.

“Well, to use Depeche Mode as an example, they went from a very poppy band to having kind of a deeper and darker sound. Did that encourage those bands to go to Berlin looking for this sort of Cold War coldness? Or did going there impart that on music?” Alex asked.

In response, Daniel recalled going to Hanser, a famous studio near the Berlin Wall.

“Hanser was right by the wall, so there was a lot of actor things going on, kind of on the level that didn’t relate to real life, but nevertheless you felt it,” but bands didn’t go there to discover “Cold War coldness,” he said.

“So the first thing was that it’s a great studio. The first album that I worked on, with Depeche Mode, was Construction Time Again. That was the first one we did in Berlin. Gareth Jones was the engineer on the record, and he just moved to Berlin and had been working there.”

He continued: “London was pretty grim in those days, and if you finished working at 11 o’clock at night, it’s kind of when we finished up, there was nothing to do in London. Everything was closed.”

By contrast, Berlin was, and remains, a 24-hour city. After working the studio late, Daniel and the band could go out and get a drink.

“So, we could go out and have a drink or fight, whatever we felt like after being in the studio, and there were some great bars there, a lot of the local German musicians work in the bars there, and so we go to know the people, local musicians.”

Depeche Mode actually started recording Construction Time Again in The Garden, the studio once owned by John Foxx in Shoreditch, London, Daniel said. Gareth Jones had helped John.

“John Fox is also really a great guy, a great musician, and he built the studio. It felt like a studio built by a musician, not one built by an engineer,” Daniel said.

Stream Construction Time Again by Depeche Mode on Spotify:

In the interview, Alex expressed his love of Laibach, and he wanted to know how Mute came to work with the band.

“We had our very first ever office, which was like a shop front in the west-end of London, Seymour Place, and they just wandered in one day,” Daniel said. “And they were super young, and they didn’t play me music. They just showed me their artwork.”

Although intrigued, Daniel could not commit to working with the young group.

“I was pretty much in the studio every day of the year. It’s an incredible thing, but Depeche Mode released five albums in five years, and did five world tours, so we were constantly in the studio, not just with Depeche but a lot of people. I just didn’t have the time to sign and work with new artists.”

Eventually, Laibach returned to Mute, and Daniel agreed to work with them on their album Opus Dei.

In 2015, Daniel traveled with Laibach to North Korea, where the band became the first-ever Western rock group to perform in Pyongyang North Korea’s capital.

“This is definitely not a defense of North Korea in any way, I’m just saying how I saw it. People looked like, pretty much how they would look in any other region or city. And there were incredible monumental buildings that had no real purpose apart from being monumental and being a tribute to a great leader,” Daniel said.

Daniel took some pictures of the trip, and The Guardian newspaper published them as a photographic account of Laibach’s journey.

In the weeks prior to the interview, Alex reached out to some musicians and other luminaries who know Daniel to ask them about the importance of Mute, and they supplied him with some testimonials. Alex surprised Daniel with these testimonials during the interview, and here are a few of them.

Hugo Burnham from Gang of Four said, “Daniel was a sightly mysterious man who wrote and produced fabulous songs, and who signed or managed a bunch of fabulously musicians.”

Barry Adamson, once of Magazine, Visage, The Birthday Party, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, and Pan Sonic, said, “Daniel gave me the keys to the soundtrack city. By believing in me, I was able to branch off in a whole new direction and I owe it all to him.”

We agree that Daniel Miller is indeed an innovator who has elevated the art of electronic music. Cheers, Daniel!

Here are some pictures of Daniel Miller in interview at Moogfest 2019 on April 26, 2019.